Classical mechanics

In physics, classical mechanics is one of the two major sub-fields of mechanics, which is concerned with the set of physical laws describing the motion of bodies under the action of a system of forces. The study of the motion of bodies is an ancient one, making classical mechanics one of the oldest and largest subjects in science, engineering and technology.

Classical mechanics describes the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, as well as astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. Besides this, many specializations within the subject deal with gases, liquids, solids, and other specific sub-topics. Classical mechanics provides extremely accurate results as long as the domain of study is restricted to large objects and the speeds involved do not approach the speed of light. When the objects being dealt with become sufficiently small, it becomes necessary to introduce the other major sub-field of mechanics, quantum mechanics, which reconciles the macroscopic laws of physics with the atomic nature of matter and handles the wave-particle duality of atoms and molecules. In the case of high velocity objects approaching the speed of light, classical mechanics is enhanced by special relativity. General relativity unifies special relativity with Newton's law of universal gravitation, allowing physicists to handle gravitation at a deeper level.

The term classical mechanics was coined in the early 20th century to describe the system of physics begun by Isaac Newton and many contemporary 17th century natural philosophers, building upon the earlier astronomical theories of Johannes Kepler, which in turn were based on the precise observations of Tycho Brahe and the studies of terrestrial projectile motion of Galileo. Because these aspects of physics were developed long before the emergence of quantum physics and relativity, some sources exclude Einstein's theory of relativity from this category. However, a number of modern sources do include relativistic mechanics, which in their view represents classical mechanics in its most developed and most accurate form. [note 1]

The initial stage in the development of classical mechanics is often referred to as Newtonian mechanics, and is associated with the physical concepts employed by and the mathematical methods invented by Newton himself, in parallel with Leibniz, and others. This is further described in the following sections. Later, more abstract and general methods were developed, leading to reformulations of classical mechanics known as Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics. These advances were largely made in the 18th and 19th centuries, and they extend substantially beyond Newton's work, particularly through their use of analytical mechanics. Ultimately, the mathematics developed for these were central to the creation of quantum mechanics.

Contents |

Description of the theory

The following introduces the basic concepts of classical mechanics. For simplicity, it often models real-world objects as point particles, objects with negligible size. The motion of a point particle is characterized by a small number of parameters: its position, mass, and the forces applied to it. Each of these parameters is discussed in turn.

In reality, the kind of objects that classical mechanics can describe always have a non-zero size. (The physics of very small particles, such as the electron, is more accurately described by quantum mechanics). Objects with non-zero size have more complicated behavior than hypothetical point particles, because of the additional degrees of freedom—for example, a baseball can spin while it is moving. However, the results for point particles can be used to study such objects by treating them as composite objects, made up of a large number of interacting point particles. The center of mass of a composite object behaves like a point particle.

Position and its derivatives

| The SI derived "mechanical" (that is, not electromagnetic or thermal) units with kg, m and s |

|

| Position | m |

| Angular position/Angle | unitless (radian) |

| velocity | m s−1 |

| Angular velocity | s−1 |

| acceleration | m s−2 |

| Angular acceleration | s−2 |

| jerk | m s−3 |

| "Angular jerk" | s−3 |

| specific energy | m2 s−2 |

| absorbed dose rate | m2 s−3 |

| moment of inertia | kg m2 |

| momentum | kg m s−1 |

| angular momentum | kg m2 s−1 |

| force | kg m s−2 |

| torque | kg m2 s−2 |

| energy | kg m2 s−2 |

| power | kg m2 s−3 |

| pressure and energy density | kg m−1 s−2 |

| surface tension | kg s−2 |

| Spring constant | kg s−2 |

| irradiance and energy flux | kg s−3 |

| kinematic viscosity | m2 s−1 |

| dynamic viscosity | kg m−1 s−1 |

| Density(mass density) | kg m−3 |

| Density(weight density) | kg m−2 s−2 |

| Number density | m−3 |

| Action | kg m2 s−1 |

The position of a point particle is defined with respect to an arbitrary fixed reference point, O, in space, usually accompanied by a coordinate system, with the reference point located at the origin of the coordinate system. It is defined as the vector r from O to the particle. In general, the point particle need not be stationary relative to O, so r is a function of t, the time elapsed since an arbitrary initial time. In pre-Einstein relativity (known as Galilean relativity), time is considered an absolute, i.e., the time interval between any given pair of events is the same for all observers. In addition to relying on absolute time, classical mechanics assumes Euclidean geometry for the structure of space.[1]

Velocity and speed

The velocity, or the rate of change of position with time, is defined as the derivative of the position with respect to time or

.

.

In classical mechanics, velocities are directly additive and subtractive. For example, if one car traveling East at 60 km/h passes another car traveling East at 50 km/h, then from the perspective of the slower car, the faster car is traveling east at 60 − 50 = 10 km/h. Whereas, from the perspective of the faster car, the slower car is moving 10 km/h to the West. Velocities are directly additive as vector quantities; they must be dealt with using vector analysis.

Mathematically, if the velocity of the first object in the previous discussion is denoted by the vector u = ud and the velocity of the second object by the vector v = ve, where u is the speed of the first object, v is the speed of the second object, and d and e are unit vectors in the directions of motion of each particle respectively, then the velocity of the first object as seen by the second object is

Similarly,

When both objects are moving in the same direction, this equation can be simplified to

Or, by ignoring direction, the difference can be given in terms of speed only:

Acceleration

The acceleration, or rate of change of velocity, is the derivative of the velocity with respect to time (the second derivative of the position with respect to time) or

Acceleration can arise from a change with time of the magnitude of the velocity or of the direction of the velocity or both. If only the magnitude v of the velocity decreases, this is sometimes referred to as deceleration, but generally any change in the velocity with time, including deceleration, is simply referred to as acceleration.

Frames of reference

While the position and velocity and acceleration of a particle can be referred to any observer in any state of motion, classical mechanics assumes the existence of a special family of reference frames in terms of which the mechanical laws of nature take a comparatively simple form. These special reference frames are called inertial frames. An inertial frame is such that when an object without any force interactions(an idealized situation) is viewed from it, it will appear either to be at rest or in a state of uniform motion in a straight line. This is the fundamental definition of an inertial frame. They are characterized by the requirement that all forces entering the observer's physical laws originate in identifiable sources (charges, gravitational bodies, and so forth). A non-inertial reference frame is one accelerating with respect to an inertial one, and in such a non-inertial frame a particle is subject to acceleration by fictitious forces that enter the equations of motion solely as a result of its accelerated motion, and do not originate in identifiable sources. These fictitious forces are in addition to the real forces recognized in an inertial frame. A key concept of inertial frames is the method for identifying them. For practical purposes, reference frames that are unaccelerated with respect to the distant stars are regarded as good approximations to inertial frames.

Consider two reference frames S and S' . For observers in each of the reference frames an event has space-time coordinates of (x,y,z,t) in frame S and (x′,y′,z′,t′) in frame S′. Assuming time is measured the same in all reference frames, and if we require x = x' when t = 0, then the relation between the space-time coordinates of the same event observed from the reference frames S′ and S, which are moving at a relative velocity of u in the x direction is:

- x′ = x − ut

- y′ = y

- z′ = z

- t′ = t

This set of formulas defines a group transformation known as the Galilean transformation (informally, the Galilean transform). This group is a limiting case of the Poincaré group used in special relativity. The limiting case applies when the velocity u is very small compared to c, the speed of light.

The transformations have the following consequences:

- v′ = v − u (the velocity v′ of a particle from the perspective of S′ is slower by u than its velocity v from the perspective of S)

- a′ = a (the acceleration of a particle is the same in any inertial reference frame)

- F′ = F (the force on a particle is the same in any inertial reference frame)

- the speed of light is not a constant in classical mechanics, nor does the special position given to the speed of light in relativistic mechanics have a counterpart in classical mechanics.

For some problems, it is convenient to use rotating coordinates (reference frames). Thereby one can either keep a mapping to a convenient inertial frame, or introduce additionally a fictitious centrifugal force and Coriolis force.

Forces; Newton's second law

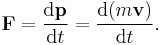

Newton was the first to mathematically express the relationship between force and momentum. Some physicists interpret Newton's second law of motion as a definition of force and mass, while others consider it to be a fundamental postulate, a law of nature. Either interpretation has the same mathematical consequences, historically known as "Newton's Second Law":

The quantity mv is called the (canonical) momentum. The net force on a particle is thus equal to rate change of momentum of the particle with time. Since the definition of acceleration is a = dv/dt, the second law can be written in the simplified and more familiar form:

So long as the force acting on a particle is known, Newton's second law is sufficient to describe the motion of a particle. Once independent relations for each force acting on a particle are available, they can be substituted into Newton's second law to obtain an ordinary differential equation, which is called the equation of motion.

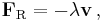

As an example, assume that friction is the only force acting on the particle, and that it may be modeled as a function of the velocity of the particle, for example:

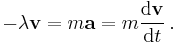

where λ is a positive constant. Then the equation of motion is

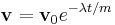

This can be integrated to obtain

where v0 is the initial velocity. This means that the velocity of this particle decays exponentially to zero as time progresses. In this case, an equivalent viewpoint is that the kinetic energy of the particle is absorbed by friction (which converts it to heat energy in accordance with the conservation of energy), slowing it down. This expression can be further integrated to obtain the position r of the particle as a function of time.

Important forces include the gravitational force and the Lorentz force for electromagnetism. In addition, Newton's third law can sometimes be used to deduce the forces acting on a particle: if it is known that particle A exerts a force F on another particle B, it follows that B must exert an equal and opposite reaction force, −F, on A. The strong form of Newton's third law requires that F and −F act along the line connecting A and B, while the weak form does not. Illustrations of the weak form of Newton's third law are often found for magnetic forces.

Work and energy

If a constant force F is applied to a particle that achieves a displacement Δr,[note 2] the work done by the force is defined as the scalar product of the force and displacement vectors:

More generally, if the force varies as a function of position as the particle moves from r1 to r2 along a path C, the work done on the particle is given by the line integral

If the work done in moving the particle from r1 to r2 is the same no matter what path is taken, the force is said to be conservative. Gravity is a conservative force, as is the force due to an idealized spring, as given by Hooke's law. The force due to friction is non-conservative.

The kinetic energy Ek of a particle of mass m travelling at speed v is given by

For extended objects composed of many particles, the kinetic energy of the composite body is the sum of the kinetic energies of the particles.

The work-energy theorem states that for a particle of constant mass m the total work W done on the particle from position r1 to r2 is equal to the change in kinetic energy Ek of the particle:

Conservative forces can be expressed as the gradient of a scalar function, known as the potential energy and denoted Ep:

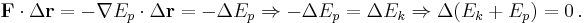

If all the forces acting on a particle are conservative, and Ep is the total potential energy (which is defined as a work of involved forces to rearrange mutual positions of bodies), obtained by summing the potential energies corresponding to each force

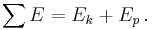

This result is known as conservation of energy and states that the total energy,

is constant in time. It is often useful, because many commonly encountered forces are conservative.

Beyond Newton's laws

Classical mechanics also includes descriptions of the complex motions of extended non-pointlike objects. Euler's laws provide extensions to Newton's laws in this area. The concepts of angular momentum rely on the same calculus used to describe one-dimensional motion. The rocket equation extends the notion of rate of change of an object's momentum to include the effects of an object "losing mass".

There are two important alternative formulations of classical mechanics: Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics. These, and other modern formulations, usually bypass the concept of "force", instead referring to other physical quantities, such as energy, for describing mechanical systems.

The expressions given above for momentum and kinetic energy are only valid when there is no significant electromagnetic contribution. In electromagnetism, Newton's second law for current-carrying wires breaks down unless one includes the electromagnetic field contribution to the momentum of the system as expressed by the Poynting vector divided by c2, where c is the speed of light in free space.

History

Some Greek philosophers of antiquity, among them Aristotle, founder of Aristotelian physics, may have been the first to maintain the idea that "everything happens for a reason" and that theoretical principles can assist in the understanding of nature. While to a modern reader, many of these preserved ideas come forth as eminently reasonable, there is a conspicuous lack of both mathematical theory and controlled experiment, as we know it. These both turned out to be decisive factors in forming modern science, and they started out with classical mechanics.

The medieval “science of weights” (i.e., mechanics) owes much of its importance to the work of Jordanus de Nemore. In the Elementa super demonstrationem ponderum, he introduces the concept of “positional gravity” and the use of component forces.

The first published causal explanation of the motions of planets was Johannes Kepler's Astronomia nova published in 1609. He concluded, based on Tycho Brahe's observations of the orbit of Mars, that the orbits were ellipses. This break with ancient thought was happening around the same time that Galilei was proposing abstract mathematical laws for the motion of objects. He may (or may not) have performed the famous experiment of dropping two cannon balls of different weights from the tower of Pisa, showing that they both hit the ground at the same time. The reality of this experiment is disputed, but, more importantly, he did carry out quantitative experiments by rolling balls on an inclined plane. His theory of accelerated motion derived from the results of such experiments, and forms a cornerstone of classical mechanics.

As foundation for his principles of natural philosophy, Newton proposed three laws of motion: the law of inertia, his second law of acceleration (mentioned above), and the law of action and reaction; and hence laid the foundations for classical mechanics. Both Newton's second and third laws were given proper scientific and mathematical treatment in Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which distinguishes them from earlier attempts at explaining similar phenomena, which were either incomplete, incorrect, or given little accurate mathematical expression. Newton also enunciated the principles of conservation of momentum and angular momentum. In Mechanics, Newton was also the first to provide the first correct scientific and mathematical formulation of gravity in Newton's law of universal gravitation. The combination of Newton's laws of motion and gravitation provide the fullest and most accurate description of classical mechanics. He demonstrated that these laws apply to everyday objects as well as to celestial objects. In particular, he obtained a theoretical explanation of Kepler's laws of motion of the planets.

Newton previously invented the calculus, of mathematics, and used it to perform the mathematical calculations. For acceptability, his book, the Principia, was formulated entirely in terms of the long established geometric methods, which were soon to be eclipsed by his calculus. However it was Leibniz who developed the notation of the derivative and integral preferred today.

Newton, and most of his contemporaries, with the notable exception of Huygens, worked on the assumption that classical mechanics would be able to explain all phenomena, including light, in the form of geometric optics. Even when discovering the so-called Newton's rings (a wave interference phenomenon) his explanation remained with his own corpuscular theory of light.

After Newton, classical mechanics became a principal field of study in mathematics as well as physics. After Newton there were several re-formulations which progressively allowed a solution to be found to a far greater number of problems. The first notable re-formulation was in 1788 by Joseph Louis Lagrange. Lagrangian mechanics was in turn re-formulated in 1833 by William Rowan Hamilton.

Some difficulties were discovered in the late 19th century that could only be resolved by more modern physics. Some of these difficulties related to compatibility with electromagnetic theory, and the famous Michelson-Morley experiment. The resolution of these problems led to the special theory of relativity, often included in the term classical mechanics.

A second set of difficulties were related to thermodynamics. When combined with thermodynamics, classical mechanics leads to the Gibbs paradox of classical statistical mechanics, in which entropy is not a well-defined quantity. Black-body radiation was not explained without the introduction of quanta. As experiments reached the atomic level, classical mechanics failed to explain, even approximately, such basic things as the energy levels and sizes of atoms and the photo-electric effect. The effort at resolving these problems led to the development of quantum mechanics.

Since the end of the 20th century, the place of classical mechanics in physics has been no longer that of an independent theory. Emphasis has shifted to understanding the fundamental forces of nature as in the Standard model and its more modern extensions into a unified theory of everything.[2] Classical mechanics is a theory for the study of the motion of non-quantum mechanical, low-energy particles in weak gravitational fields.

In the 21st century classical mechanics has been extended into the complex domain and complex classical mechanics exhibits behaviours very similar to quantum mechanics.[3]

Limits of validity

Many branches of classical mechanics are simplifications or approximations of more accurate forms; two of the most accurate being general relativity and relativistic statistical mechanics. Geometric optics is an approximation to the quantum theory of light, and does not have a superior "classical" form.

The Newtonian approximation to special relativity

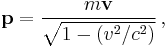

In special relativity, the momentum of a particle is given by

where m is the particle's mass, v its velocity, and c is the speed of light.

If v is very small compared to c, v2/c2 is approximately zero, and so

Thus the Newtonian equation p = mv is an approximation of the relativistic equation for bodies moving with low speeds compared to the speed of light.

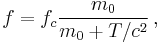

For example, the relativistic cyclotron frequency of a cyclotron, gyrotron, or high voltage magnetron is given by

where fc is the classical frequency of an electron (or other charged particle) with kinetic energy T and (rest) mass m0 circling in a magnetic field. The (rest) mass of an electron is 511 keV. So the frequency correction is 1% for a magnetic vacuum tube with a 5.11 kV direct current accelerating voltage.

The classical approximation to quantum mechanics

The ray approximation of classical mechanics breaks down when the de Broglie wavelength is not much smaller than other dimensions of the system. For non-relativistic particles, this wavelength is

where h is Planck's constant and p is the momentum.

Again, this happens with electrons before it happens with heavier particles. For example, the electrons used by Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer in 1927, accelerated by 54 volts, had a wave length of 0.167 nm, which was long enough to exhibit a single diffraction side lobe when reflecting from the face of a nickel crystal with atomic spacing of 0.215 nm. With a larger vacuum chamber, it would seem relatively easy to increase the angular resolution from around a radian to a milliradian and see quantum diffraction from the periodic patterns of integrated circuit computer memory.

More practical examples of the failure of classical mechanics on an engineering scale are conduction by quantum tunneling in tunnel diodes and very narrow transistor gates in integrated circuits.

Classical mechanics is the same extreme high frequency approximation as geometric optics. It is more often accurate because it describes particles and bodies with rest mass. These have more momentum and therefore shorter De Broglie wavelengths than massless particles, such as light, with the same kinetic energies.

Branches

Classical mechanics was traditionally divided into three main branches:

- Statics, the study of equilibrium and its relation to forces

- Dynamics, the study of motion and its relation to forces

- Kinematics, dealing with the implications of observed motions without regard for circumstances causing them

Another division is based on the choice of mathematical formalism:

Alternatively, a division can be made by region of application:

- Celestial mechanics, relating to stars, planets and other celestial bodies

- Continuum mechanics, for materials which are modelled as a continuum, e.g., solids and fluids (i.e., liquids and gases).

- Relativistic mechanics (i.e. including the special and general theories of relativity), for bodies whose speed is close to the speed of light.

- Statistical mechanics, which provides a framework for relating the microscopic properties of individual atoms and molecules to the macroscopic or bulk thermodynamic properties of materials.

See also

Notes

- ^ The notion of "classical" may be somewhat confusing, insofar as this term usually refers to the era of classical antiquity in European history. While many discoveries within the mathematics of that period remain in full force today, and of the greatest use, much of the science that emerged then has since been superseded by more accurate models. This in no way detracts from the science of that time, though as most of modern physics is built directly upon the important developments, especially within technology, which took place in antiquity and during the Middle Ages in Europe and elsewhere. However, the emergence of classical mechanics was a decisive stage in the development of science, in the modern sense of the term. What characterizes it, above all, is its insistence on mathematics (rather than speculation), and its reliance on experiment (rather than observation). With classical mechanics it was established how to formulate quantitative predictions in theory, and how to test them by carefully designed measurement. The emerging globally cooperative endeavor increasingly provided for much closer scrutiny and testing, both of theory and experiment. This was, and remains, a key factor in establishing certain knowledge, and in bringing it to the service of society. History shows how closely the health and wealth of a society depends on nurturing this investigative and critical approach.

- ^ The displacement Δr is the difference of the particle's initial and final positions: Δr = rfinal − rinitial.

References

- ^ MIT physics 8.01 lecture notes (page 12) (PDF)

- ^ Page 2-10 of the Feynman Lectures on Physics says "For already in classical mechanics there was indeterminability from a practical point of view." The past tense here implies that classical physics is no longer fundamental.

- ^ Complex Elliptic Pendulum, Carl M. Bender, Daniel W. Hook, Karta Kooner

Further reading

- Feynman, Richard (1996). Six Easy Pieces. Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-201-40825-2.

- Feynman, Richard; Phillips, Richard (1998). Six Easy Pieces. Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-201-32841-0.

- Feynman, Richard (1999). Lectures on Physics. Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-7382-0092-1.

- Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1972). Mechanics Course of Theoretical Physics , Vol. 1. Franklin Book Company. ISBN 0-08-016739-X.

- Eisberg, Robert Martin (1961). Fundamentals of Modern Physics. John Wiley and Sons.

- Fundamental university physics. Addison-Wesley.

- Structure and Interpretation of Classical Mechanics. MIT Press. 2001. ISBN 0-262-19455-4.

- An Introduction to Mechanics. McGraw-Hill. 1973. ISBN 0-07-035048-5.

- Classical Mechanics (3rd ed.). Addison Wesley. 2002. ISBN 0-201-65702-3.

- Thornton, Stephen T.; Marion, Jerry B. (2003). Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems (5th ed.). Brooks Cole. ISBN 0-534-40896-6.

- Kibble, Tom W. B.; Berkshire, Frank H. (2004). Classical Mechanics (5th ed.). Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-86094-424-6.

External links

- Crowell, Benjamin. Newtonian Physics (an introductory text, uses algebra with optional sections involving calculus)

- Fitzpatrick, Richard. Classical Mechanics (uses calculus)

- Hoiland, Paul (2004). Preferred Frames of Reference & Relativity

- Horbatsch, Marko, "Classical Mechanics Course Notes".

- Rosu, Haret C., "Classical Mechanics". Physics Education. 1999. [arxiv.org : physics/9909035]

- Schiller, Christoph. Motion Mountain (an introductory text, uses some calculus)

- Shapiro, Joel A. (2003). Classical Mechanics

- Sussman, Gerald Jay & Wisdom, Jack & Mayer,Meinhard E. (2001). Structure and Interpretation of Classical Mechanics

- Tong, David. Classical Dynamics (Cambridge lecture notes on Lagrangian and Hamiltonian formalism)

- Kinematic Models for Design Digital Library (KMODDL)

Movies and photos of hundreds of working mechanical-systems models at Cornell University. Also includes an e-book library of classic texts on mechanical design and engineering. - MIT OpenCourseWare 8.01: Classical Mechanics Free videos of actual course lectures with links to lecture notes, assignments and exams.